Bangladesh: A Multisensory Experience

I spent 15 days in Bangladesh, visiting the cities of Dhaka, Saidpur, Sylhet, Rangpur, Khulna, Barisal, Cox’s Bazar, and lots of sites and towns in the surrounding areas.

Before traveling, I didn’t research as I would have liked, so I was going into it blind. My only point of reference was the extended period I’d spent in 1989-1990 traveling throughout India.

To understand my observations over those fifteen days, I found it helpful to first step back and view Bangladesh in the abstract: the numbers, the rankings, the basic facts that define the place from afar.

Overview

Population (2024) - 173.6 million

Population Growth Rate (2024) - 1.2%

Size - 148,460 k2 (57,320 sq mi) - about the size of the state of Illinois or a bit bigger than Nepal

GDP (nominal 2024) - $432.7 billion

GDP per capita (nominal 2024) - $2,527.50

GDP per capita PPP - $10,260

Inflation rate (2024) - 10.5%

Biggest export - readymade garments (2nd largest in the world)

Median age (2024) - 29.6 years

Life expectancy (female/male) - 76.7/73.3

Murder rate (2020) - 2.3/100K

Founded - 1971

Ethnicity - 99% Bengali, 1% other indigenous ethnic groups

Religion - 91% Muslim, 8% Hindu, 1% other

Corruption Perceptions Index - Rank #151/180

Index of Economic Freedom - Rank #122/184

The Geography of Water

Those numbers only relay part of the story. To understand Bangladesh, you have to start with its physical reality: water, and a lot of it.

Bangladesh is the spot on earth where the world’s largest mountains drain into the sea. It is a flat, humid delta dominated by the Ganges and Brahmaputra river systems.

This geography has often positioned the region as an imperial outpost rather than a dominant center of power. India completely envelopes it, save for a small, volatile strip bordering Myanmar in the southeast.

The border itself is symbolic of the chaos in the country. Drawn hastily during the 1947 Partition by the British (who prioritized leaving quickly over settling the issue), the line zigzags over 2,500 miles. For decades, this resulted in some of the most complex border arrangements in modern history: the enclaves.

There were islands of India inside Bangladesh, and islands of Bangladesh inside India—and even islands inside the islands. With little care for land titles, they became de facto “no man’s lands.” Residents had no citizenship, no police, no schools, and no hospitals. It wasn’t until a land swap in 2015 that both countries mostly resolved this cartographic madness.

The Bloody Birth

The Short Version:

Partition (1947): The British divide India. Bengal is split. East Bengal became “East Pakistan.” The Hindu elite (zamindars), who owned 75% of the land, mostly fled to India.

The Void: West Pakistanis filled the administrative vacuum, treating the Bengalis as second-class citizens, suppressing their language, and exploiting their jute exports to fund development in the country’s west.

The Breaking Point (1971): The Awami League (East) won the national election. West Pakistan refused to accept the results and launched “Operation Searchlight,” an attempt to snuff out Bengali nationalism.

The resulting 1971 Liberation War was horrific. Estimates of the dead range from 300,000 to 3 million. Pakistani forces systematically used rape as a weapon of war (200,000–400,000 victims) and targeted intellectuals and Hindus to decapitate the society.

This trauma continues to shape politics today. The Awami League (led recently by Sheikh Hasina) monopolized the “Liberation” narrative, using the power of the state to equate the party with the country’s independence and labeling all opposition as “anti-liberation” traitors. The method proved successful initially, yet Hasina’s regime turned dictatorial—silencing the media, imprisoning opponents, and controlling the judiciary—leading to mass protests that ousted her in 2024.

When I visited, the country was in the tenuous air of a “reset,” currently under the caretaker government of Muhammad Yunus.

The Economy

Out of that violence and political upheaval emerged a fragile, crowded state that still had to answer a basic question: how do 170-plus million people make a living on this wet, overworked patch of earth?

Garments: If you are wearing H&M, Zara, or Uniqlo, your clothes were likely stitched here. It is the second-largest garment exporter in the world.

Remittances: Millions of young men work construction in the Gulf or service jobs in Southeast Asia, sending cash home.

The Fish Pivot: This is a fascinating microeconomic shift. Rice farming used to be the only game in town (Bangladeshis eat ~400 lbs of rice a year). But recently, farmers realized that digging a hole in the rice paddy to grow catfish, carp, and tilapia could yield 5x the profit of rice and provide a richer diet. The countryside is now a patchwork of netted ponds providing cheap protein to the masses.

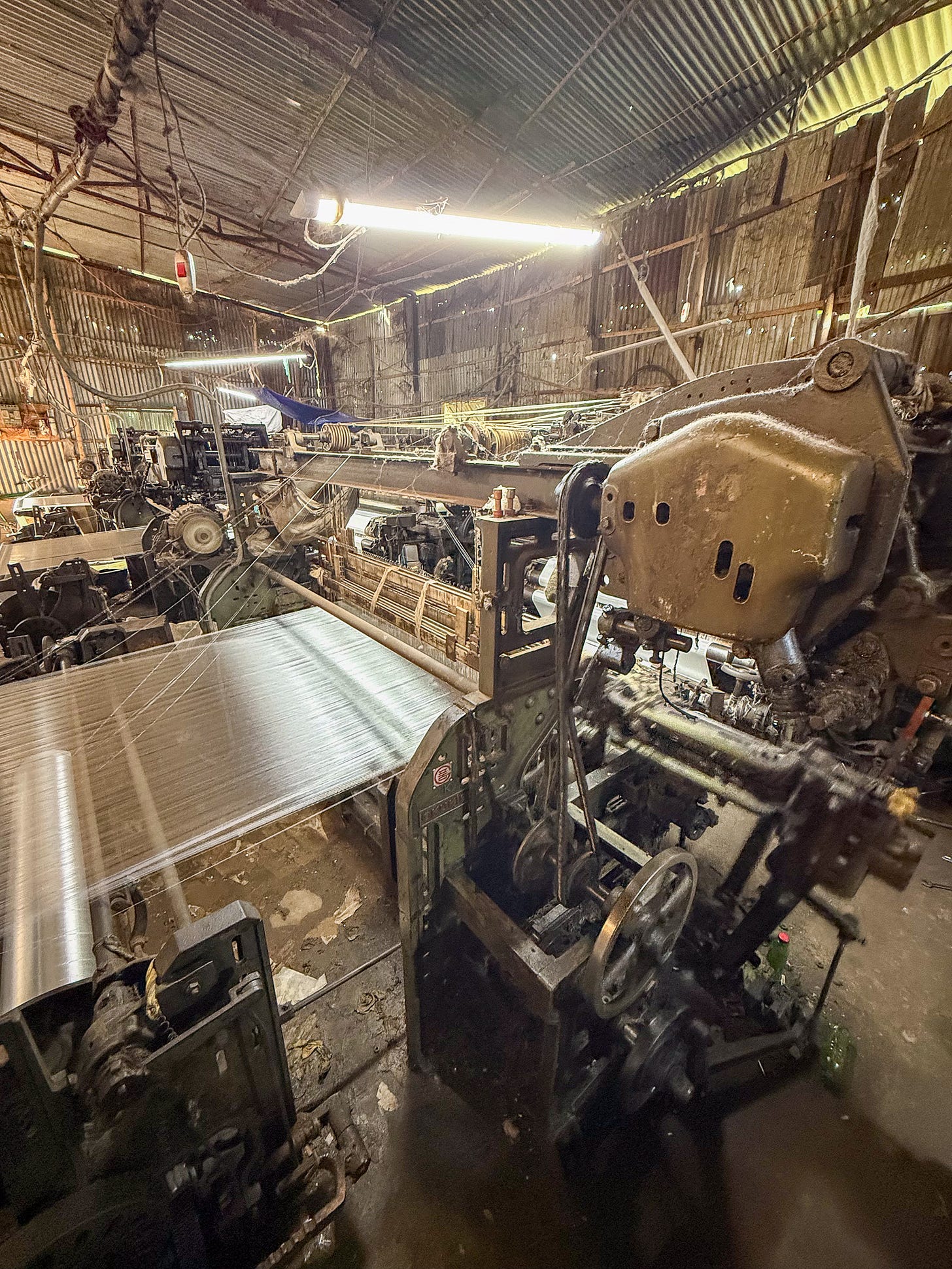

We visited a workshop where they were making saris by hand. I was amazed at how the workers had the patterns in their heads, despite how intricate they were. My second observation was that the strong machines were near each other, always moving, and extraordinarily powerful. I could imagine someone’s single mistake ending badly, like in a Sinclair Lewis book.

Impressions: The Chaos

That economic story sounds abstract until you hit the streets of Dhaka, where the country’s survival strategies show up as sound, motion, and sheer density.

Arriving in Dhaka, all my senses were struck at once - horns blaring from cars, buses, and rickshaws stuck in endless traffic. Humidity and heat sapped my energy, vibrantly painted and decorated rickshaws competing against double-decker buses that seemed 50% repair compound. Trash is everywhere, but I struggled to find a trash can. One of the few I discovered had a massive hole in the bottom where the trash continued through to the ground.

Above you, the electrical infrastructure hangs in terrifying, chaotic knots ten feet off the ground—a mess that the internet age has only compounded. “Double-decker” buses weave through streets, resembling DIY projects, and avoid ornate rickshaws.

Religion and “Embracing the Orange”

Once you look past the tangled wires and honking buses, what starts to stand out isn’t just the traffic—it’s the call to prayer, the mosques tucked into neighborhoods, and the small religious details coloring daily life.

Bangladesh is 91% Muslim, and purportedly has become increasingly orthodox. However, the flavor of Islam here is distinct from that in the Middle East.

Architecture: In the Gulf, mosques are projections of state power—massive stone edifices. In Bangladesh, stone is rare. Everything is clay. Thus, the historic mosques are terracotta. They are squat, intimate, community-level buildings designed to survive the monsoon, not to intimidate.

The Vibe: The mosques I visited were all welcoming. Imams were friendly, gave us impromptu tours of the grounds, and made conversation. In Saidpur, locals woke up an imam at night just to unlock a mosque for my group to see. He seemed happy to do so and allowed us to climb the towers and walk around unsupervised.

The Visual Marker: You will see older men everywhere with bright orange beards. This is henna. It’s a specific Hadith interpretation common in South Asia: the Prophet encouraged dyeing hair to distinguish Muslims from Christians and Jews, and henna was the approved method. In the Gulf, men ignore this and dye their beards jet black; here, they embrace the orange.

The Rohingya

In the southeast, near Cox’s Bazar, lies one of the world’s current great messes.

Over one million Rohingya refugees live here, fleeing war in Myanmar’s Rakhine state. It is the world’s largest refugee camp, a sprawling city of bamboo and tarp. The Bangladeshi government, hostile to their presence, has laws in place that ban employment, education, and permanent structures hoping to get the Rohingya to return.

The geopolitical situation here is bleak. The Rohingya are stuck between the military of Myanmar and the Arakan Army. Bangladesh wants them out. The US and UN provide aid (though funding is chronically short), but the political will to solve the root cause in Myanmar has been largely absent.

Minorities and Identity

Standing in those camps, it’s easy to see identity as something contested at the borders. But the same struggle over religion, language, and belonging also plays out within Bangladesh’s own borders.

Though Bangladesh was created with linguistic nationalism (Bengali) and secularism in mind, it’s now more religiously exclusive.

The Hindu population has plummeted from nearly 30% at Partition to 8% today. The wealthy Hindu zamindars are long gone, leaving mostly lower-caste Namashudras. Hindus are often targeted during political instability, including events like the 1971 war and the 2024 revolution.

There is an ongoing debate since the formation of the country: Are we Bengali (an ethnic identity shared with India’s West Bengal) or Bangladeshi (a distinct Muslim national identity)? At this point in history, the emphasis on a distinct Muslim national identity dominates official discourse and policy.

Food

I seemed to eat a lot of Indian food while I was there. Even biryanis on the menu were dishes like Hyderabad biryani. The blurring on the plate reflects a larger cultural overlap, a shared Bengali world.

Fish and rice are the staples of the diet. The national dish is Ilish (Hilsa), a fish from the Padma River. The Bangladeshis are very proud of it. I’m not a big fish eater, but I tried it one night, and it was good. The waiter warned me about the bones, but they didn’t bother me.

Otherwise, if I was eating Bengali food, it was a mutton biryani, usually.

Conclusion

I arrived in Bangladesh with little preparation, carrying a three-decade-old mental map of India and not much else. What I found was a country that overlaps with India in language, food, and history, but is also its own dense, crowded, improvisational world built on water and trauma.

Rivers explain a lot: the constant threat of floods, the patchwork of fish ponds and rice fields, the sense that everything is temporary and must be rebuilt again and again. The politics explain a lot too: a nation established in conflict, still arguing over who gets to speak for its “liberation,” and what it means to be Bengali or Bangladeshi. The economy feels like a survival strategy more than a grand design—garment factories, remittances, and fish farms all trying to stretch limited land and capital across 170-plus million lives.

On the street, that all collapses into a single sensory experience: the honking, the heat, the chaos of traffic, the trash that has nowhere obvious to go, the terrifying electrical knots overhead. And yet, within that mess are people who kept opening doors—imams waking up in the middle of the night to show us a mosque, workers weaving impossibly intricate saris, strangers who were curious, proud, and often eager to talk and snap photos with me.

The contradictions are there. A welcoming, overwhelmingly Muslim society that periodically closes in on minorities. A country hosting one of the world’s largest refugee populations while struggling to provide for its own. A place where the state often feels distant or predatory, but where community and religious life remain strong and local.

It goes without saying: fifteen days isn’t long enough to claim understanding of a place this complicated. But it was long enough to shake loose my old comparisons and force me to see Bangladesh on its own terms: not as India’s poorer cousinbut as a specific, battered, scrappy delta where history, water, and sheer human density collide.