The Danakil Depression: Where Earth Tears Itself Apart

A Journey Through Ethiopia's Volcanic Lowlands in the Aftermath of Eruption and War

I pressed my palms into the jagged crust at Lake Karum and felt the salt crystals bite into my skin as I hauled myself out of the brine. The water—warm, viscous, buoyant—had held me like a pair of hands, but the edges of the hole were salty glass shards. Blood welled up behind my knees, bright red against the white ground. I stood there in the afternoon sun, watching it spread, rubbing salt into my wounds.

A Land Remaking Itself

I’d come to the Danakil Depression because the earth here was tearing itself apart, and I wanted to see what that looked like. This corner of Ethiopia sits at the junction of three tectonic plates pulling in different directions, and the last year had been violent. Hayli Gubbi erupted in November 2025 for the first time in recorded history, sending ash so high it grounded flights in India. Erta Ale, the lava lake that glowed red for decades, had exploded in July and gone dark. The land remade itself in real time.

Descent from the Highlands

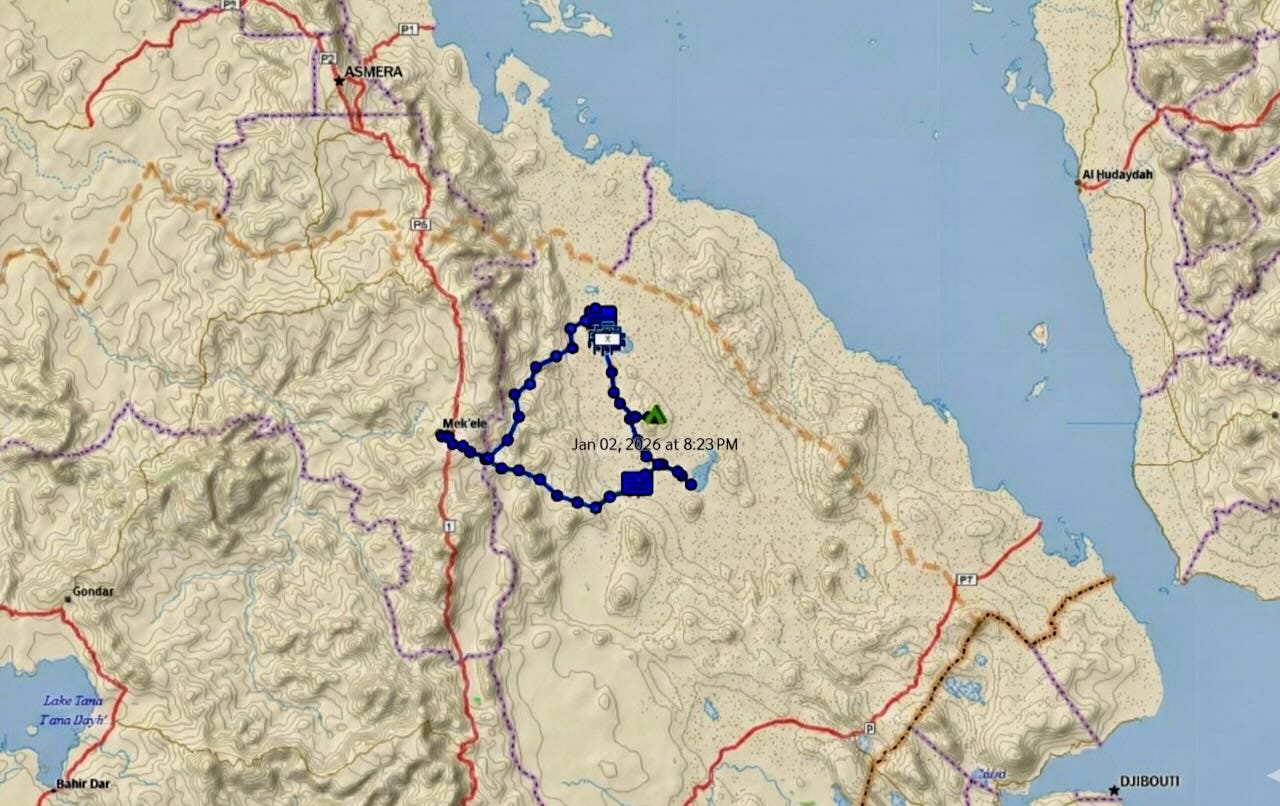

But there was another rift here too, one that had ended in name only. We started in the Tigrayan highlands at 7,400 feet, where women in white habesha libs walked along the roadside, their hair braided in tight, intricate rows. Our white Land Cruiser—the kind you see in every conflict zone—had a large sticker of a crossed-out rifle on the door. In a region still raw from the 2020-2022 war, that sticker mattered.

The highway down into the Afar lowlands carved through the side of the escarpment in tight switchbacks. The altitude fell toward sea level, and the Orthodox churches disappeared. In their place: minarets. The white cotton dresses gave way to neon—fuchsia, electric yellow, acid green—the Afar women moving through the desert like tropical birds in a landscape drained of color.

Bordering on Resentment

The tension was evident close to Abaala, the border town. Tigrayan forces had pushed through here during the fighting, and the resentment hadn’t dissipated. We stopped at multiple checkpoints where guards with rifles scanned our vehicle, looking for insurgents or weapons. I saw only the surface - the suspicious glances and curt conversation. The actual stories behind the rifles and roadblocks passed by, and our car sped on.

Life in the Dust

After the towns, the landscape opened into an emptiness that surprised me. The Afar have lived here for millennia, nomadic herders moving with their livestock across a terrain that looks like it should be uninhabitable. Their homes—ari—are portable domes made from lashed branches, which in better years get covered in woven palm mats. But the drought has gone on so long that now most of the ari I saw were clad in white plastic sheeting or patched together from woven plastic fodder bags, flapping and snapping in the hot wind. The women build these structures, and when the water vanishes, they dismantle them and load them onto camels to move somewhere just as unforgiving.

The salt defines this place. We stopped at Lake Afrera, 112 meters below sea level, which sat there like a wound in the earth—deep emerald green, fed by scalding hot springs. I swam for a few minutes in warm water four times saltier than the ocean, slick against my skin like oil. In the center of the lake sat the lowest-lying island on the planet, a tiny speck of rock in a basin of brine.

But the volcanoes were what I’d come for. We drove north along a volcanic range past Hayli Gubbi, which spent November 2025 throwing ash into the stratosphere. The lava flows swallowed grazing land and left behind fields of black glass that crunched underfoot. Nothing would grow there for generations.

Erta Ale was stranger. For decades, people trekked here to stare into a persistent lake of molten rock—the “Gateway to Hell” they called it. But the massive July explosion reshaped everything. When I reached the rim after a 30-minute walk across sharp basalt in the dark, there was no red glow. The lava lake either retreated deep underground or hid beneath tons of fresh debris. What remained was vog—thick volcanic smog that burned the back of my throat and turned the moon into a pale, smoky orange disc.

The Laws of Heat

Dallol was the ultimate stop, the lowest and hottest place in Ethiopia. We wound through salt canyons where erosion carved the earth into towering fluted pillars, beige and white like church organ pipes.

Then Dallol itself: a hydrothermal field of neon yellows, electric greens, rust reds. Boiling water vented through pillars of salt and sulfur. There were no railings, no signs, no shade. The smell of rotten eggs hung in the air, and the earth hissed. It was a landscape of pure chemistry—beautiful and hostile. It was beautiful and horrific, smelling like death and danger. Standing there, the geopolitics of the highlands seemed like something from another planet. Here, the only laws were heat and the slow, inevitable movement of tectonic plates. Geology doesn’t take sides. The land shifts because it has to. The people, maybe, don’t.

On the climb back toward the Tigrayan mountains, leaving the white salt pans of Lake Karum behind, the wounds on my legs burned. The Danakil doesn’t let you leave without a mark.

So you finally did it, congrats!

Fascinating land. Would love to one day see that and the Ethiopia you describe.