Frankfurt: The New Old Town

Reconstructing the Past in Frankfurt

The first time you travel to Germany, you stroll through a picturesque old town and run across a beautiful medieval church. You feel surrounded by history. If you are an American, you are blown away at the age of everything in Europe; in your country, “old” might mean a one hundred years. But then you read the plaque. It tells you that Allied bombing destroyed the church in World War II and the city rebuilt it in recent decades.

This keeps happening in place after place in Germany, and then it becomes clear. You grasp the sheer scale of the destruction that occurred here and how much history and culture was erased.

Was there an alternative? I don’t know, and I won’t second-guess the people who made those decisions during the war. City centers and villages evolve organically; new buildings arise, old ones are torn down, and heritage boards decide what’s historically significant. But beyond the architecture, I think of the family losses—the personal memories, the photos, the heirlooms that vanished in the inferno.

This brings us to a hard question: How do we handle what was lost? Reconstruction can be a powerful tool for memory, but it walks a fine line. It risks creating a comfortable, nostalgic version of the past that ignores what happened afterward.

Nowhere is this tension more real than in Frankfurt am Main.

The Lost Heart of the City

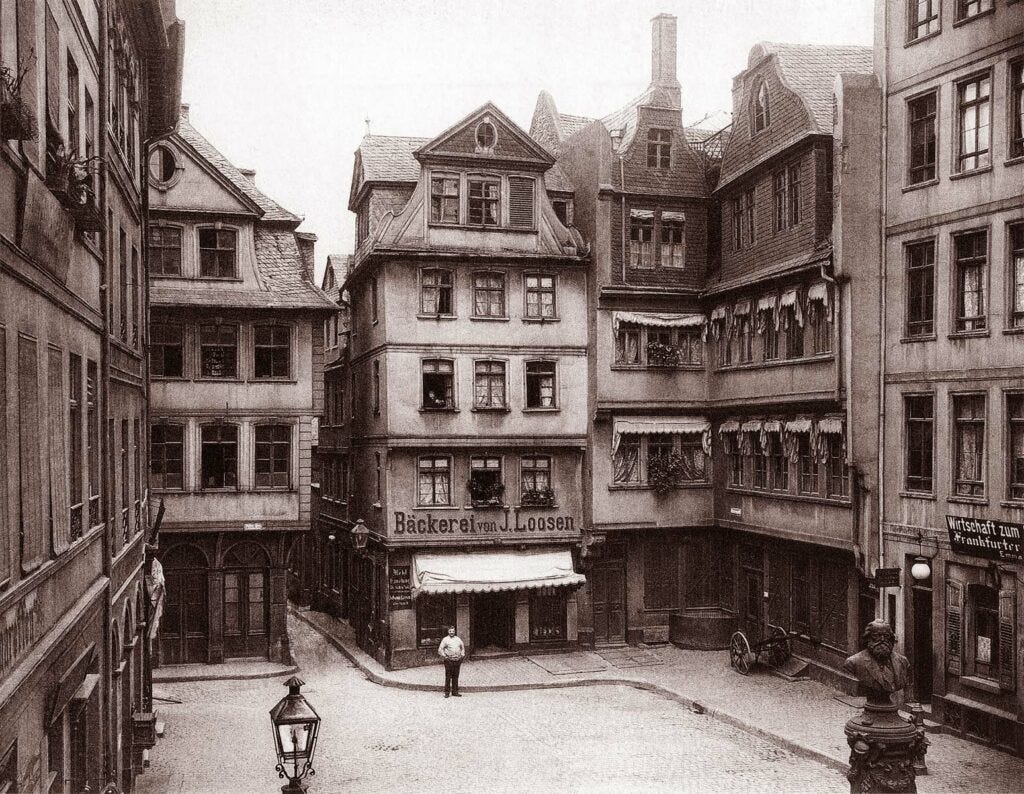

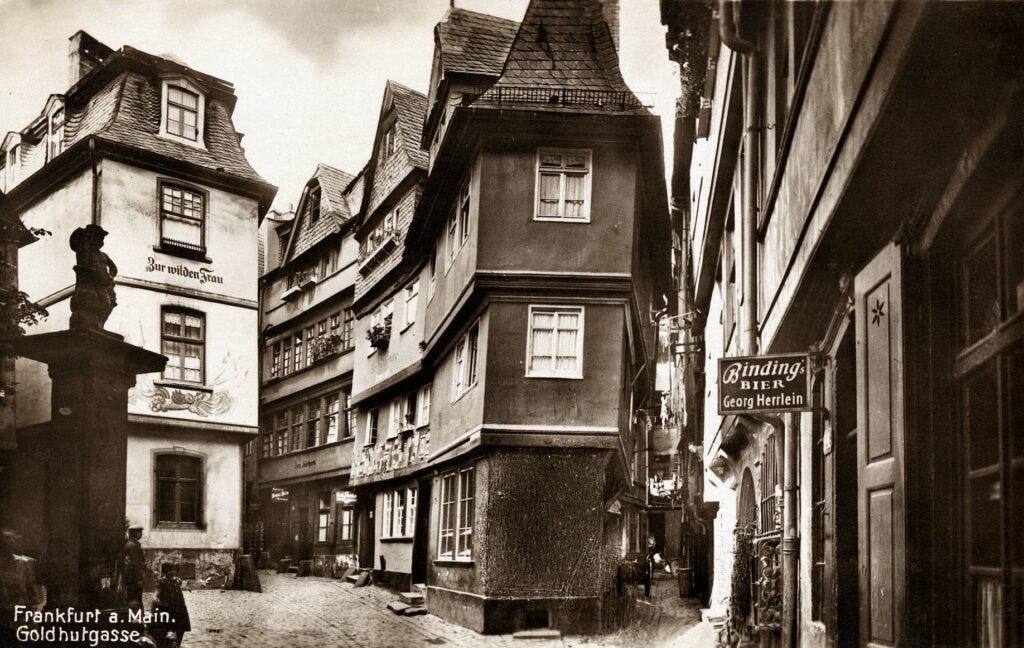

Frankfurt ought to be a place of major historical importance. It was the site of the election of every Holy Roman Emperor of the German state since 1356. Celebrations of the empire took place at the Römer and the Frankfurt Cathedral. In the 1800s, even as Frankfurt became an industrial city, the Altstadt stayed a living museum of the Holy Roman Empire.

But that medieval core was obliterated. The British Royal Air Force acted on a directive of “de-housing” and demoralizing German workers, operating under the strategic belief that destroying the fabric of daily life would break the country’s will and end the war faster. German historic centers, with their timber-framed structures, were vulnerable to this tactic. Although the Allies had policies regarding cultural preservation, historical records show these were consistently subordinated to “military necessity.”

On March 22, 1944, the old city died. Frankfurt was home to the largest half-timbered old town in Germany, but in a single night, nearly 2,000 medieval buildings were obliterated. The tight, winding medieval blocks were gone. The Daily Express labeled Frankfurt “the most bombed city in the world”.

A Modern Identity Crisis

When the war ended, German cities grappled with how to move forward. While often framed as a binary choice—faithful reconstruction versus radical modernization—reality offered many more possibilities. Cities could try a layered approach: restoring key monuments while filling the gaps with contemporary architecture, preserving the medieval street grid while changing the skyline, or even leaving ruins as “honest” markers of the devastation. In Frankfurt, however, the debate was polarized from the start.

There was immediate tension between the modernizers and the rebuilders. For decades, the modernizers mostly won. Some sites like the Römer and the Paulskirche were rebuilt in a simplified style; most were not reconstructed. Germans in Frankfurt had a desire to break from the past and opt for radical modernization. The large area between the cathedral and the Römer was a parking lot for almost thirty years. In the early 1970s, the city built a massive concrete city hall in the space that effectively erased the original layout of the old town.

However, in 2007, the Frankfurt city council pivoted, based on public dislike of the concrete buildings and desire to tap into the city’s history. They underwent a significant rebuilding of the Altstadt using the street grid of the late Middle Ages. In 2010, they tore down the city hall and other Brutalist buildings from the 1970s. The construction of fifteen historic buildings was completed in 2018 with original plans. But they have also added twenty new buildings in the space. They have resurrected history, but curated and adjudicated it simultaneously.

This is the “New Old Town” (Dom-Römer-Viertel). The buildings look old, yet the stone is only ten years old.

Museum, Disneyland, or…

Walking through these streets raises tough questions. Critics argue that this is the “museumification” of a city center—an architectural Disneyland that prioritizes tourism over authenticity. There is also the question of selective memory: by rebuilding the charming medieval center, are we glossing over the darker chapters of history that led to its destruction?

These are legitimate concerns. Prioritizing looks over facts could cause us to lose sight of the city’s actual history. Even the concrete buildings tell the story of post-war Frankfurt

However, I see immense value in these efforts, provided they are handled with transparency. The New Old Town isn’t the medieval Altstadt, and we shouldn’t pretend it is. But it can be a faithful map of it.

I don’t have a problem with historic reconstructions; in my travels, I have found that even replicas can teach us a great deal about a culture—how people lived, how they built, and what they valued. But accuracy is key. This means not just copying the facade, but being honest about the materials, the context, and the gap in time.

I have seen questionable (in my mind) reconstructions around the world - in Addis Ababa where a modernizing government has torn down and reconfigured the Piazza; the Globe Theater in London is a 1997 reconstruction; and the Gothic Quarter of Barcelona contains facades attached to the fronts of plain residential buildings.

Countries need to move forward, but they must also give their citizens the opportunity to have a tangible sense of where they came from. Balancing the needs of a modern city with the memory of its origins is a delicate task. Frankfurt’s New Old Town is one city’s carefully considered attempt to bridge that gap.